The Black Patch

The Forgotten Kingdom of American Dark Fired Tobacco

And the Night Riders Who Fought Back

Most cigar smokers have heard of Connecticut Shade. Very few have heard of the Black Patch. This stretch of land across western Kentucky and northwest Tennessee once produced some of the strongest and most influential tobacco in the world. Its barns filled the air with the smell of hickory and oak. Its farmers built a thriving way of life. And when a powerful monopoly tried to choke the region into submission, the people here did not go quietly. They rose up and became known as the Night Riders.

This is the story of the Black Patch. A story born in smoke and soil. A story of families who fought to survive. A story America forgot.

The Land That Created Dark Fired Tobacco

The Black Patch is anchored by small towns like Hopkinsville, Elkton, Guthrie, Clarksville, Springfield, and Russellville. The soil in these counties is dark and rich. The summers are heavy and humid. Everything about this land invites tobacco to grow thick and strong.

Dark fired tobacco is not like the golden leaves of Connecticut Shade. Here the leaves cure inside tall barns where slow fires burn for days. Hickory logs crackle on the dirt floor. Smoke rises up through the rafters until every leaf turns deep and oily. The result is a powerful tobacco with a sweetness and strength that almost no other region can produce.

Families like the Brewers, McReynolds, Fowlers, Stokes, and Grubbs built their lives around this work. Generations planted the same fields, tied the same hands of tobacco, and fired the same barns. The Black Patch became its own world, shaped by fire and family.

When the Monopoly Arrived

By the end of the eighteen hundreds the region was thriving, and that success attracted the attention of one of the most powerful industrialists in the country. James Buchanan Duke controlled the American Tobacco Company, a corporation that swallowed up competitors and controlled nearly every part of the tobacco market. When Duke focused his attention on the Black Patch, the farmers quickly discovered what it meant to face a monopoly.

The company fixed prices so low that no farm could survive. Families who had weathered droughts, storms, and lean harvests found themselves crushed by a buyer who could dictate the price of their labor. Entire communities were pushed to the edge of ruin.

The farmers tried peaceful negotiation. They organized and pleaded for fair prices. Nothing changed. Duke’s company would not loosen its grip. And that is when the Black Patch reached a breaking point.

The Rise of the Night Riders

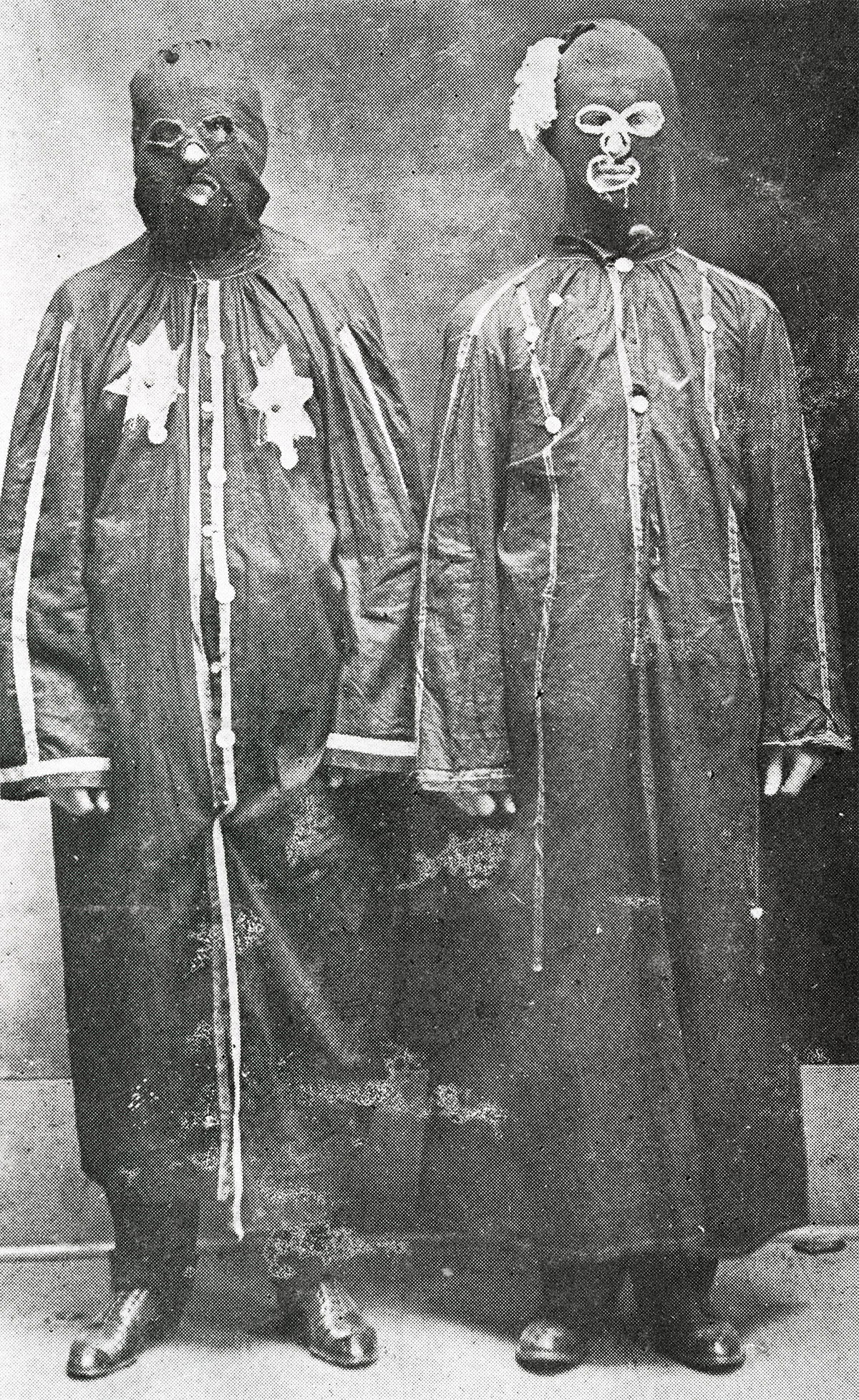

The struggle gave birth to one of the most dramatic chapters in agricultural history. Out of the frustration and desperation of the farmers came a group who called themselves the Night Riders.

They rode after dark across the back roads and farm lanes. Many covered their faces with cloth or pulled their hats low. They moved with a purpose that came from fear of losing everything they had ever known. These men believed that if they did not fight back, their land, their homes, and their futures would disappear.

The Night Riders targeted the monopoly and the farmers who cooperated with it. Barns used by the American Tobacco Company were set on fire. Warehouses that stored the Trust’s tobacco were destroyed. Riders thundered into towns like Hopkinsville and Princeton and forced the monopoly to feel the cost of its chokehold on the region.

The most dramatic moment came in December of 1907 when hundreds of Night Riders entered Hopkinsville. They overtook the police, burned Duke’s facilities, and drove out the company men who had taken control of local trade. People still talk about that night as if the riders rode through yesterday.

The War Ends and a Strange Twist Appears

The violence lasted for several years until federal antitrust action finally broke up the American Tobacco Company in 1909. The monopoly fell apart. The farmers finally had room to breathe. The Black Patch won its freedom, but the conflict left deep marks that never truly faded.

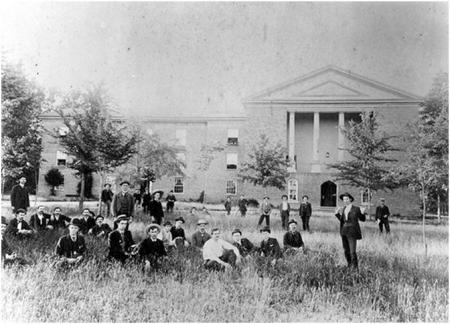

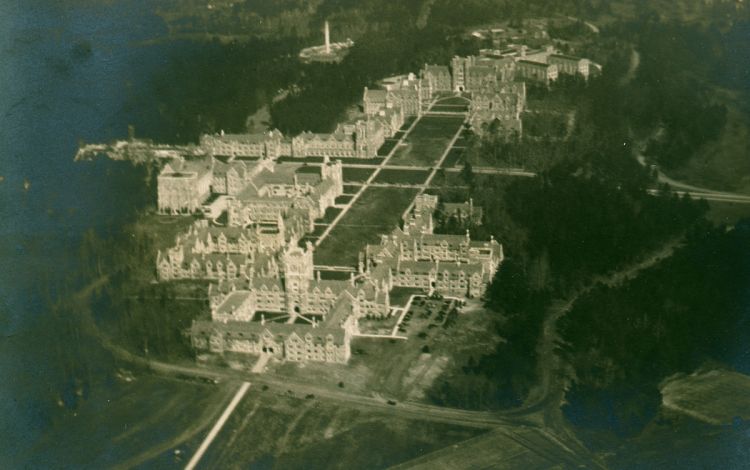

And here is the part of the story most people never hear. James B. Duke, the same man whose monopoly sparked the Black Patch War, became one of the wealthiest men in America. In 1924 he gave an enormous endowment to Trinity College in Durham, North Carolina. The donation was so large that the trustees renamed the entire institution Duke University in his honor. Duke never asked them to do it. The school chose to rename itself because the gift was so transformative.

So the man who nearly crushed the Black Patch forever is the same man whose name now sits on one of the country’s most prestigious universities. History has a long memory and sometimes a dark sense of irony.

The Golden Age and the Long Decline

After the monopoly fell, the Black Patch entered a golden age. Through the nineteen twenties and thirties and into the postwar years, the region produced some of the finest dark fired tobacco in the world. Barns glowed at night with the fires of curing season. Families taught their children how to tie hands of tobacco the same way their grandparents had done.

But slowly the decline began. Federal buyouts encouraged farmers to exit the industry. Regulations increased. Cigarette companies shifted their blends. Cigar factories moved to Central America. The land that once held nearly one hundred thousand acres of dark fired tobacco saw its fields shrink to a fraction of that number.

Many barns collapsed under their own weight. Many families left farming forever. The Black Patch faded from national memory.

The Survivors and the Legacy

Even now a small number of families continue the tradition in Christian County, Todd County, Montgomery County, and Robertson County. They still raise real dark fired tobacco with wood fires and hard labor. They still know the smell of a curing barn in the middle of the night. They carry a heritage few Americans even realize exists.

The history of the Black Patch is not just about tobacco. It is a story of people who refused to be crushed. It is a reminder that American tobacco has a past worth remembering. And it is a testament to the Night Riders, men who fought back when no one else would.

0 comments